Acts chapter 11 describes the push of the gospel from its Jewish beginnings into the Gentile world with the founding of the church at Antioch in Syria. Chapter 10, as you know, tells us how the Roman centurion Cornelius was instrumental for Peter’s own schooling on the idea that “God is not one to show partiality” (Acts 10:34) and that he should not call Gentiles “unholy or unclean” (Acts 10:28). (Whew ... good thing!)

And here in Acts 11:19–30, a strategic center for the church’s expansion into the Gentile world is established. News of God’s work at Antioch (Luke is keen to show this is God’s work at every turn) reaches Jerusalem, and Barnabas, the “Son of Encouragement,” is dispatched. When he arrives and “witnesses the grace of God,” he rejoices (11:23), and then gets to work joining in what God is already doing.

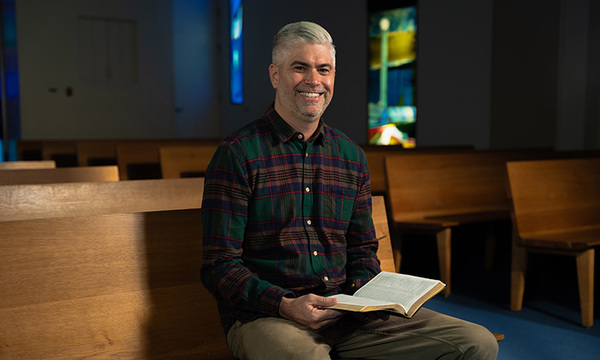

This scene of Barnabas encountering such beginnings there in Antioch describes well Talbot’s Kyiv extension in Ukraine. Now in our 11th year, we’re a little further down the road from the raw beginnings Barnabas witnessed there in Antioch, but it is clear the grace of God is at work in Ukraine and the greater Slavic world (as he always is at work! See Hab. 1:5). And for this, we all have good reason to rejoice. In these few pages, allow me to highlight for you what I see as the fruit of God’s work and the opportunity Talbot has had to encourage that fruit, so that you too can be like Barnabas and rejoice in the grace of God.

1. Ukraine: The Slavic World’s Antioch?

From its beginnings in the gospel’s movement among Gentiles in Acts 11, Antioch continues to fulfill its role as Acts unfolds. In chapter 13, the missionary venture to the Gentiles that Paul and Barnabas would undertake begins from this church (Acts 13:1). And it will remain something of Paul’s sending church throughout the book. It is to this church he is especially keen to report the work of the Lord in his missionary journeys. And when the church needed to settle the critical theological question of the gospel’s relationship to the Law of Moses, it was the church at Antioch that was ground zero for raising the issue with the apostles and elders of Jerusalem (Acts 15). So, by mission and theology, this place looms large in the Christian story.

In my 25 years of living and traveling often to Ukraine, I cannot help but see many parallels with Antioch. No, we’re not talking about something quite as epic as launching the gospel to the Gentile world, but as a theological church and mission center to the 11 time zones of the former Soviet Union, there is something to be said for the church of Ukraine.

Back when my wife and I were just signing on to work in the newly opened fields of Eurasia in the early ’90s, Ukraine was then known as the “Bible Belt” of the Soviet Union. Our time there proved it over and over. Ukrainian Baptists were evangelizing and church-planting maniacs! — I remember the early totals were consistently something like 150 new churches every year — and for a country the size of our Pacific Northwest! Those numbers of course have slowed in the interim and the church today wrestles greatly with building up its flock in the grace and knowledge of God, but no other place where Russian is the lingua franca was close to this level of activity. The Ukrainian church was also a beehive for establishing theological training centers like Kyiv Theological Seminary (KTS), host of the Talbot extension. In 2000, I remember hearing that Kyiv itself was the headquarter to 40 different Western mission agencies and Christian groups, many of which were starting theological education projects. At one point, there were four theological seminaries up and running by different groups, a couple of Christian universities and scores of other Bible institutes and other church-based programs in Kyiv alone. And this kind of activity was typical for all of Ukraine in stark comparison to the other recently freed countries.

Of course, the Christian landscape of Ukraine and Kyiv looks different today. A natural selection process has eliminated some duplicate schools; finances have dried up for others driven by early Western zeal; and Ukrainians, who have now had their chance at higher education, are effectively running their own training and missionary efforts. But the point is Ukraine is still a special place for the work of the gospel in the Slavic world. Not only are the early efforts of evangelizing and training paying dividends with their own biblically trained and zealous workforce now decades out, but of all the former Soviet countries to the east, Ukraine remains the freest politically. Against the Muslim hegemony in the “Stans” (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, etc.) or the Orthodox in the Russian Federation, Ukraine’s government does not hinder the gospel’s proclamation — in fact, it’s gotten easier there! And this is all still in the context of a couple of revolutions (Orange Revolution, 2005; and now Revolution of Dignity, 2014) and four-year terrorist-separatist occupation from the Russian Federation in the southeastern part of the country.

In this unique setting, God seems to have called Talbot to play a modest role. And we rejoice at the grace of God. Back in 2003, when Anatoly Propkopchuk, rector and founder of KTS, first approached Talbot’s dean, Dennis Dirks, about a partnership, he was looking for two things. As he still describes it, the “wasteland” left by the Communists on the Slavic Christian infrastructure requires partners from the West for training and theological resources to flourish and serve the church. Theological education at the time was a very haphazard project with “everyone doing what was right in their own eyes,” to steal an aphorism from the time of Israel’s judges. And while there were attempts at standardization from a fledgling accrediting group that had been in operation for some time (Euro-Asia Accrediting Association, E-AAA), it seemed the ability to go to the level of a doctrinally healthy and legitimate credentialed master’s degree was elusive in the region. Anatoly asked Talbot to enter and establish norms for solid evangelical education. This meant not only doing everything necessary to get an extension program cleared by Talbot’s accreditors — a three-year task in itself, it also meant engaging all of the education systems below that would be potential feeders to the graduate level. This was the tedious task that Biola’s graduate admissions office took on to establish norms for equivalency between what was happening in the Slavic world in theological education and what would pass for entrance to Talbot’s graduate program. So, Talbot’s presence meant not only a fully accredited graduate program for biblical and theological studies in the region — the only one to this day (there is now thankfully a graduate-level and accredited counseling, chaplaincy and pastoral program — and all in Ukraine), but it also meant much in upgrading and standardizing bachelor’s programs in the region who wanted their graduates to be able to enter Talbot. With Talbot’s partnership, Anatoly moved theological training to the next level and also strengthened what was already happening at KTS and other schools. Now a bachelor’s degree had something behind it, too.

The other thing Anatoly was seeking from Talbot was an answer to extraction. Missiologists know the term well as the label for the situation when a region’s brightest and most capable go abroad to continue studies but never return. They either come back, and because they have so adapted to the lifestyle of the places they’ve gone (America or Europe), re-entry is too diffcult that they soon leave again; or they end up finding work abroad and never come back at all. Anatoly himself was one of the rare ones who had returned after his Master of Theology from Dallas Theological Seminary, but many like him did not make the flight back, or if they did, they are no longer in Ukraine. Without graduate-level theological training available in the Eurasian regions, the pace of extraction would continue. Talbot’s presence in Ukraine brings a two-fold answer to extraction. First, the Kyiv extension runs classes in intensive modules four times a year. Students come in for two weeks for course content with their professors and then return to their homes to complete their assignments. Online courses have now entered the mix reducing the need for travel even more for some students. Second, Talbot offers students a 95 percent tuition discount to extension students (which I don’t share much with our students at Biola’s campus in La Mirada). Even the five percent obligation is a stretch for these students with their average monthly salary of $200, but without it, they have no chance at something more.

2. Educating the Educators.

Experts in intercultural engagements of all kinds, whether it be in politics, business or Christian missions, all tout the critical value of contextualization. Without an understanding of the cultural context, long-term effectiveness will always be a challenge. And the biggest part of contextualization means listening to those in the host culture. What is their assessment of the need and its resolution? What are they asking for?

As I mentioned already, Anatoly had specific educational priorities he was looking for in a partnership with Talbot. Talbot had to come, but Talbot also had to listen for the Slavic context it was entering. The result of that listening is the unique shape of the Kyiv extension’s master’s in biblical and theological studies degree. When it came time to talk seriously about what courses would be offered at the extension, then Talbot Dean Dirks practically handed the catalog to Anatoly and gave him carte blanche — how can we help? Anatoly, wide-eyed like a kid on Christmas, drew things up around what he saw as the Slavic evangelical church’s greatest needs — deep knowledge of the Bible, biblical theology, and church history, because of the Orthodox church context. Talbot’s own value for spiritual formation was added to the mix in two courses that have proven to be a refreshing and life-giving answer to issues students didn’t even know they had but were real nonetheless. And we were off!

That was now 11 years ago, and the time interim gives a chance to reflect and rejoice in what the Lord is doing through our 23 current students and 21 alumni, as well as Talbot faculty, who have had a chance to be part of this grace of God. Following are four areas where the Talbot-Kyiv Extension encourages the grace of God in the church of Eurasia.

- Vocational, local church ministry. Talbot’s commitment to education to serve local churches is reflected in the Kyiv extension’s student body. Indeed, interviews for student admissions turn heavily on this point, so 95 percent of current students and alumni are presently active in their local church ministry, with nearly 40 percent in their church’s pastoral ministry. Because of their common passion for local church ministry, students tell us that coming to Kyiv for sessions is catalytic for their shared ministry experience beyond what’s going on in their classes. The 2 a.m. dorm discussions generate ideas, foster off-campus collaborations and provide solace and counsel from empathetic listeners when needed. Extension students and alumni in church leadership positions also means virtually immediate impact to local church life as what’s caught during a session can go right out the following week in sermons, Bible studies, men’s and women’s groups, children’s and outreach ministries.

- Academic and parachurch ministry. Kyiv extension students’ impact on the local church is rivaled only by their activity within theological education projects throughout the region. As members of a relatively small cadre of people with this level of education, extension students and grads are in demand for leading regional seminaries, Bible colleges and institutes. Eighty percent of alumni and 78 percent of current students are active in theological education projects, in addition to their church work. This applies to all levels, including deans or presidents at four major institutions, to program directors, regular teachers and lecturers, to library and department staff. Most fill these roles in Ukraine, but the Talbot extension now has two graduates doing mission work in Poland and students from the Russian Federation and Kazakhstan who fulfill their ministry and academic tasks back in their homeland when they’re not in Kyiv for sessions. Clearly at this time, at least, it is certain that God is using no one program for shaping the future of strategic evangelical theological education as the Talbot-Kyiv Extension.

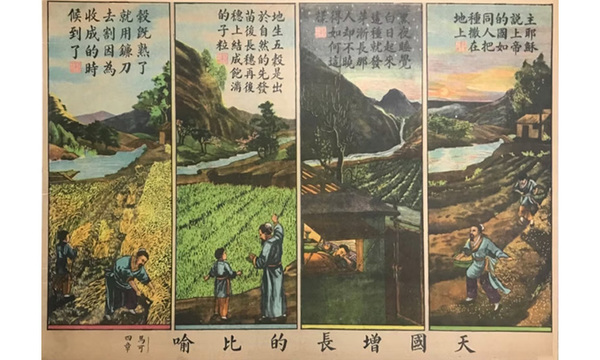

- Publishing ministry. Opportunities for theological training at this level also makes Kyiv extension graduates and students candidates for serving their churches through writing and publishing. A recent and bold publishing project sponsored through the E-AAA is a good example. The Slavic Bible Commentary that just came out in 2016 offers commentary on every book of the Bible from Slavic writers. Kyiv extension grads and staff contributed sections on Joshua, Psalms (in part), Daniel, Jonah, Micah, Haggai and Zechariah. Academic essays from extension graduates and students regularly appear in the Ukrainian theological journal, Theological Reflections. And due to the initiative of Vladimir Yakim, the extension’s assistant director, the exegetical works of students from an OT prophets course that Vladimir taught in the extension last year will appear in a series of future volumes. Kyiv extension faculty contributed to a Russian-language volume dedicated to the growing field of theology of work. Finally, the newest theological journal on the Eurasian scene since 2017, called Studii: A Journal of Evangelical Theology, is edited by Eduard Borysov, the Kyiv extension’s on-site director.

- Talbot ministry. The last point worth noting here — and noting “with big letters” — is the impact of working with brothers and sisters in Eurasia on Talbot’s faculty. Anyone involved with teaching knows the classroom is really the laboratory of the Holy Spirit to work on both students and teacher. He’s the one in the white coat shaping all into the image of Christ. That shaping process goes double in another culture, and it was just this experience that Dirks knew Talbot faculty would reap good from too if the Kyiv extension could get off the ground. And it is true. I speak from my own experience best here, but I get comments from my colleagues enough to know it is real with them as well. Of course, the different life story of any student refines and impacts all around it, but the questions and interactions that come from radically different cultural places can powerfully enlarge and add to loving God better with mind, heart and strength for faculty. To date, those of Talbot’s number, both former and current faculty, who have been touched by the Spirit-teacher in the Kyiv extension “classroom” include: Alan Hultberg, Ashish Naidu, Thaddeus Williams, John Coe, Richard Leyda, Rex Johnson, Judy TenElshof, Markus Zehnder, Freddy Cardoza, Ken Way, Doug Geivett, Kevin Lewis, Joe Gorra, Jon Rittenhouse, Brian Willats and myself.

3. Opening New Roads.

Back in the ’90s, when my family was living in Kyiv, and American friends would ask about the evangelical church coming out of the Communist night, my way of answering was something like, “Think about what evangelicalism looked like in America 40 years ago, and you have a start.” By that, I meant the same theological issues the Western churches were facing decades ago, the same styles of worship and social mores like style of dress and behavior, like no card-playing, movies, smoking and alcohol, were all the current scene for the churches of my new home. With one difference. Whereas conservative Protestants were still the majority part of America’s cultural landscape back in the ’50s, in countries of the former Soviet Union, that was decidedly not the case. “Baptists” were the latecomers to the dominant Orthodox culture of the Slavic world, and whereas the Communists had “quarantined” them from political life, the Orthodox had succeeded long before in branding them a heretical sect for everything else. “Baptist theological education” were words nobody in the outside world had tools to make any sense of in terms of anything legitimate, anything serious, or anything relevant.

Talbot’s presence is changing that. Eleven years ago, Talbot introduced, for the first time, a consistent flow of credentialed and highly qualified academic specialists to the educational environment and did it all in association with an indigenous Protestant theological institution, Kyiv Theological Seminary. Extension professors were not only unleashing their grads into the world of theological writing and educational ministry, but the Kyiv extension also facilitated the translation of several works by Talbot faculty that have been widely circulated. The cumulative effect has begun to place evangelical theological higher education on the region’s academic map in new ways. Since 2016, works translated and published by extension professors, Ashish Naidu and Doug Geivett, have elicited invitations for collaboration from the Department of Religious Studies at Dragomanova Pedagogical University, a very storied and prestigious university in the heart of Kyiv. The three academic conferences that have come since have built bridges and opened doors of access and influence for evangelical Protestant theological educators that could not have been imagined even 10 years ago. Beyond the conferences, last year Dragomanova proposed to the Talbot extension and KTS a joint degree program in which students of either institution could gather degree credits from courses taken at the other. And while the unique profile of Talbot and KTS students makes this collaborative degree a stretch, the very idea of it speaks volumes to a new day for evangelical theological education in the Eurasian zone. Again, we rejoice at the grace of God.

Rejoice with Us.

When Barnabas witnessed God’s work in Antioch, we read he did two things. First, he rejoiced, and second, he got busy encouraging best he could what he saw God doing. That is how we feel about the Talbot-Kyiv Extension program. God is doing God-things through his church in Eurasia, things we wouldn’t believe if we were told them just a few years ago. But they are happening now. Our sincere hope for this simple account of God’s work in the region is that you will first have cause to rejoice at the grace of God and also consider if perhaps God would have you join in what He’s already up to.

Consider partnering with us to make quality theological education available to students in Kyiv. We need to raise about $50,000 every year in order to offer scholarships that cover 95 percent of the student’s program. Here’s where you can give a one-time gift, or become a monthly donor: giving.biola.edu/talbot-kyiv.

Biola University

Biola University