Barna Group recently partnered with Impact 360 Institute in conducting an extensive study on the beliefs, attitudes and actions of American teenagers today. Of the 1,997 teenagers included in the studies, 9 percent are engaged Christians, which means they strongly agree with the following statements:

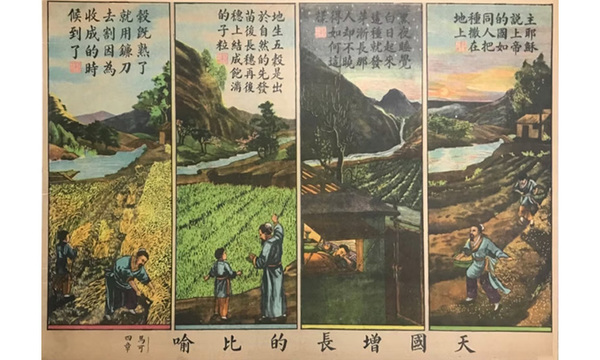

- The Bible is the inspired Word of God and contains truth about the world.

- I have made a personal commitment to Jesus Christ that is still important in my life today.

- I engage with my church in more ways than just attending services.

- I believe that Jesus Christ was crucified and raised om the dead to conquer sin and death.

Thirty-three percent are churched Christians, 16 percent are unchurched Christians, 7 percent are of other faiths and 34 percent have no religious affiliation.

Depending upon one’s read of this information, this could be either encouraging or discouraging to evangelical Christians. Fifty-nine percent of the teenagers studied are self-professing Christians, which is a high percentage. But less than 10 percent have a combination of beliefs, commitments and church involvement that evangelical Christians would like to see in young followers of Jesus. These studies indicate that there is much work for the church to do by way of discipleship and spiritual formation, along with continued evangelism.

Another aspect of these studies that is of interest is the assessment by these teens of the things very important to their sense of self. Over 40 percent indicated that professional/educational achievements and hobbies/pastimes were very important to their sense of self. At 37 percent and 35 percent, respectively, they highlighted the importance of their gender/sexuality and group of friends. Family and religion came in at 34 percent. Less important to many of these teens were their race/ethnicity (23%), local region (21%), social/economic class (13%) and political affiliation (13%). It is important to note that these are self-reported measures. So, one’s local region and socio-economic class might in fact be more formative for this group than they think it is. And certain things may be more important to one group of teens than it is to another. As the study shows, for example, race/ethnicity is much more important to racial minorities than it is to white teens. Of course, this is probably because teens in the racial majority are not often forced to think about the ways they experience their race/ethnicity whereas racial minorities are regularly compelled to do so. So, from the limited data that I have noted here, it is difficult to know what ought to be inferred from these lower percentages.

Regarding the professional/educational achievements and hobbies/pastimes that these teens take to be most important to their sense of self, perhaps we can guess at one of the reasons for this result. One might expect that teenagers would think important those things which take up the majority of their time. In other words, adults have communicated significance to their children by organizing their children’s lives around certain endeavors. Given the prominence of educational activities and hobbies (say, sports) in the days, weeks and years of a child’s life, one would expect these to be interpreted as central to their sense of self.

The fact that 34 percent indicate that religion/religious beliefs are important to their sense of self is a positive thing in this context, since often a much smaller amount of attention is given to cultivating religious beliefs and church involvement compared to educational and athletic ambitions. So, one observation that the church should make about this data is that weekly life for teenagers is often structured in ways that privilege professional/educational achievements and hobbies/pastimes, and this structure is communicating the importance of these endeavors to teens. One question that deserves more attention is the following: How should Christians structure their schedules so that the importance of Christian convictions and activities is privileged in the lives of teens? This is a vital question for the church to wrestle with moving forward.

Cultivating Excellence of Mind and Heart

We often fail to recognize the ways that our behavior reinforces cultural forms of identity-formation that are in an uneasy relationship with Christian convictions about the same. In light of this reality, a number of other questions come to the fore. Should so much of our days and weeks be given over to tasks the primary purpose of which is either money-making or physical excellence? What needs to be included in a normal day/week/ year in order to cultivate excellence of mind and heart?

I do not raise these questions as a way of diminishing the importance of work. Work is ordained by God as part of God’s good creation, as regular readers of this magazine will know. Godly investment in work is a way of investing in God’s good creation and as such it is crucial to human flourishing and to the flourishing of creation. However, money-making needs to be distinguished from work itself. There is a difference between vocationally fulfilling and important tasks for which your company is willing to compensate you and tasks that are neither vocationally fulfilling nor important for which your company is willing to compensate you. Both are ways of making money. And everyone has to do both kinds of tasks at various points. But when the majority of one’s day or week is spent doing vocationally unfulfilling work and attending to physical well-being, there may be very little time committed to spiritual and intellectual well-being. Our theology of work must cultivate a sense of the importance of profitable work but not give the idea that working for money is the sum total of one’s discipleship responsibilities. How can we make sure to communicate a proper sense of vocation and avocation to Christian teenagers?

God Defines Our Identity

There is another layer of consideration regarding human identity that requires careful attention. The church needs to wrestle with the way one’s sense of self, or identity, is construed. Our personal identities are known by God. But they are often quite difficult for us to ascertain for ourselves. This surprising experience is often the source of a great deal of anxiety. How are we supposed to understand ourselves? Does one’s personal identity come from one’s family background? Does it come from the social groups of which we are a part? Does it come from our broader social situations, perhaps from our racial, ethnic or national backgrounds?

In much of the scholarly literature, personal identities are understood to be self-constructed or socially constructed realities. From this perspective, one’s identities are fluid, being continuously cast and recast in new forms. An individual’s identities are constructed through the development of social relations, roles, values and group memberships. Self-identification with one’s family, race, ethnicity, nationality, sex, gender, religion, political perspective, etc., becomes self-defining.

From the perspective of classical Christian anthropology, however, the contemporary emphasis upon open-ended identity-formation is problematic due to features of the doctrines of creation, sin, Christology and eschatology. God is Creator and Lord, and he has determined humanity’s common identity as the creature made in God’s image and reconciled to God in Jesus Christ. According to Scripture, the effort to arrive at self-definition apart from God is sinful.

Yet, Christian anthropology has also emphasized the reality of human mutability for at least two reasons. First, humans are imperfect creatures, and imperfect creatures are necessarily mutable. This is a good thing, since change is required for an imperfect creature to arrive at perfection. Second, humans after the fall are sinful, and sin fragments human experience, exacerbating human mutability. Sin perverts human loves, and these misdirected loves conform sinners to the various objects of those loves.

Our Identity is in Christ

God’s determination of human identity and the fulfillment of that identity in Christ, as these are communicated in Scripture, should guide the personal self-interpretations of God’s people. It is important, first, to think carefully about the declared identity of humanity in Genesis 1: Humans are made in the image of God. Being made in the image of God, humans are made to reflect God’s character in the world. Second, it is important to situate our sense of self in relation to our union with Jesus Christ. Because we are united to Christ by the Holy Spirit, a Christian’s identity is bound to Jesus Christ. Moreover, our union with Christ brings about a union with Christ’s body, the church. Given these determining factors of being made in God’s image and being united to Christ, how should individuals think about their personal particularities, including all of the very important factors related to one’s personal and social backgrounds?

Often in our broader culture, the quest for personal identity is understood as a kind of self-determination. I suggest that it is better understood as a process of discovery. We are never searching for an identity that is unknown to God or unimportant to God. Yet, like all processes of discovery, sometimes what is discovered is delightful and other times it is lamentable. I may joyfully discover ways that my sense of self aligns with God’s desires and acts as they are revealed in Scripture. And I may discover ways that my sense of self is in conflict with God’s character and action. In the latter cases, I need to submit myself to the order of God’s priorities as they are expressed in Scripture.

It is helpful in this context to distinguish between creational identities and constructed identities. “Creational identities” are the fundamental truths of who God has made us to be as his creatures. “Constructed identities” are our efforts, fleeting and malleable, to make sense of our personal identities in light of the way we experience human nature in the context of our relations and roles. For Christians, the former need to condition the latter. In other words, Christians will try to discern their own places in the world, but they will do so with the larger picture of creational identities in view. This approach offers stability for a person’s sense of self. God himself is the source of this stability. His presence is the rock in a world of sand. True stability belongs only to God, since God alone is perfect life and love. But God delights to share this stability with us when we align our sense of self to his true knowledge and love revealed in Scripture.

Identity-construction can be an effort to establish a secure identity through contemplation of the self and the self’s relation to other creaturely realities. Submission of this quest to God’s determination of who we are is an act of faith. By faith, the process of identity-discovery can serve human flourishing as groups and individuals find their distinct places inside of the broader creational-recreational realities to which their identities are submitted. As we engage the generation that is beginning to graduate high school and enter young adulthood — Gen Z, as they are called — we need to cultivate attentiveness to our true identity before God as creatures made in God’s image and united to Christ, and we need to invite this young generation to understand themselves in this same light.

Includes content adapted from “Created and Constructed Identities in Theological Anthropology” by Ryan S. Peterson in The Christian Doctrine of Humanity, edited by Oliver D. Crisp and Fred Sanders. Copyright © 2018 by Oliver D. Crisp and Fred Sanders. Used by permission of Zondervan. www.zondervan.com.

Biola University

Biola University