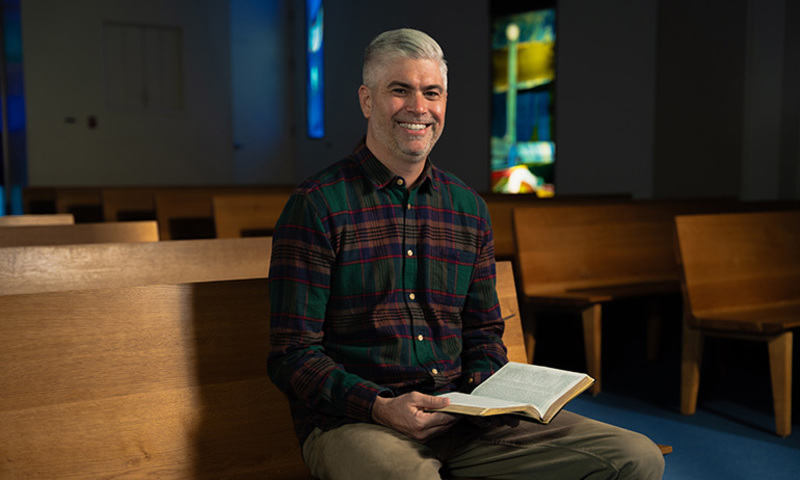

For the past 20 years, I have been privileged to serve as a pastor in various church contexts, having ministered as a youth pastor, associate pastor, and lead pastor. I have served in big and small churches, both denominational and non-denominational. While the specific people and places of my ministry have changed over the years, I know that my fundamental calling has always remained the same: Pastors are those called to care for souls in Christ by the Spirit.

It was during my time as a student at Talbot that I discovered what it truly meant to take up this calling “to shepherd the flock of God that is among you” (1 Pet. 5:1–4). Those were years of exegetical and theological training, but they were also years of spiritual and vocational formation. At Talbot, I not only discovered how to preach a sermon with doctrinal fidelity, but with love. I not only discovered how to counsel someone with biblical wisdom, but to do so as one in whom Christ’s word dwelled richly (Col. 3:16). In short, I learned what it meant to abide in a depen-dent relationship with Christ, such that the fruit of that relationship formed every dimension of my pastoral vocation.

Now, two decades later, I have the honor of contributing to Talbot’s rich history of training pastors for the unique labor of their vocation, getting to direct the pastoral care and counseling program. I have the privilege of welcoming those who have just recently discerned a call to ministry as well as those who have already taken up this calling for many years. My classes are a mix of youth pastors, associate pastors, and lead pastors from big and small churches of various evangelical denominations. Clearly, each of my students experiences unique dynamics, challenges, and oppor-tunities in and through their various church and ministry contexts. Nevertheless, what has been illuminating is not how different we all are, even with the vast range of denominations, roles, and cultural differences, but how the calling remains the same. The reason is that the pastoral calling is not fluid but fixed: they are all called to care for the souls they are among. They are all called to tend to the flock of God among them as under-shepherds of the Chief Shepherd, Jesus.

Gregory the Great tells us that “the care of souls is the art of arts” (Gregory the Great, The Pastoral Rule). In other words, it is a holy calling that requires godly wisdom. Pastors have been called by Jesus and commissioned by his church to care for souls in painful, desperate, dangerous, and consequential areas of their lives. Pastors tend to people often wracked with anxiety. They care for those habituated in dark and deviant sin. They minister to individuals in the midst of grieving great loss. They shepherd souls perplexed by spiritual desolation. They counsel those struggling to love their enemies. Pastors are called to a profoundly significant labor of love in the household God. They are a gift of Christ to his body, given to communicate his healing grace to wayward and broken joints and ligaments.

The evangelical church, in recent years, has struggled to articulate a clear understanding of pastoral care as a holy calling that requires godly wisdom. As a result, pastors often experience the care and counsel they offer as a lesser form of what their parishioners can find elsewhere. At times, pastors feel they are relegated to the role of “referral service” to better modalities of care and counseling. Sometimes, while attempting to offer something of perceived value, pastors come to believe they must mimic these other modalities of care and counseling, acting as a pseudo-therapist or life coach. If Gregory the Great is right, that the pastoral care of souls is “the art of arts,” pastoral care is never simply outsourcing the care to other modalities of care and counseling. Pastors have distinctively biblical, theological, and spiritual resources that are not only unique, but essential.

As the director of our pastoral care and counseling program at Talbot, I am committed to receiving and advancing the rich heritage of spiritual and vocational formation I discovered at Talbot years ago. Toward this end, our program will continue to emphasize the pastor’s own formation in Christ by the Spirit. Only the pastor who abides in Christ can invite others into an abiding relationship with Christ with wisdom, love, and humility. If a pastor is going to pay careful attention to the lives of others, they must be those who first “pay careful attention to [themselves]” (Acts 20:28). I am also committed to offering a renewed vision of pastoral care as “the art of arts.” Toward this end, pastors who desire to be equipped in the care of souls in Christ by the Spirit, can expect to receive a biblically normed, historically informed, and practically instructive vision for their unique and weighty vocation. Simply put, we are renewing our firm conviction that one of the fundamental and essential features of all pastoral training is pastoral care.

A renewed vision of pastoral care and counseling begins by considering and faithfully following a biblical understanding of the pastoral office. If we don’t get clear on what a pastor is, we will struggle to answer what a pastor does. Said differently, if we aren’t scripturally clear on what makes this mode of care and counseling distinctively “pastoral,” we will be left with reductive and copycat forms of care and counseling. Ultimately, we will forget this is a form of care that can only happen in Christ by the Spirit. If we lose this form of care, we will lose a distinctively Christian vision of formation, allowing the world to define “health,” while leaving our people to be tossed by the waves of whatever is new.

What we discover through this renewed excavation of the biblical material, is that the three primary titles of this particular ecclesial office are elder, overseer, and shepherd/pastor (1 Tim. 3:2–7, Titus 1:5–9, 1 Thess. 5:12, Acts 20:28, 1 Pet. 5:2). These three titles offer us a rich description of what a pastor is, which can fund our understanding of what a pastor does. As elders, pastors are called to be mature exemplars in the faith. As overseers, they are called to govern with authority and wisdom. As shepherds, they are called to protect, provide, and guide the flock in the way of Jesus. Importantly, none of these titles originate with the pastoral office — as if we just have to construct what they are with our own imagination — instead, they are first and foremost defined by Christ himself. Jesus is our true and ultimate Elder brother (Heb. 2:10–13), Overseer, and Shepherd (1 Pet. 2:25). This means that the pastoral office is, on the one hand, subordinate and derivative to Christ’s, while on the other, it is an office that participates in his continued ministry by the Spirit and that serves to bear witness to this continued work. Put differently, the way pastors elder, oversee, and shepherd, is under, from, with, and for Christ.

Pastors seeking to actively participate in the ongoing care of the risen and ascended Lord do so by knowing his counsel in their own lives; they are those who meditate on his Word, day and night (Josh. 1:8–9). Pastors seeking to be caring co-laborers of Christ, do so by personally knowing his empowering grace; they are those who prayerfully meet God in the truth of their weakness (2 Cor. 12:9). In other words, to participate, co-labor, and bear witness to the work of Christ, one’s work must lead to Christ because of the work Christ has done in your own life. Far from generically “helping people” or “leading people,” this call of shepherding is one in which the pastor rests ever more fully in the effectual grace of God. In this sense, pastoral care is given shape by the gospel. The pastor who cares for souls, never leaves the cross of Christ, but is empowered to know and live out their calling before the face of the crucified Lord of glory. It is to him that pastors shepherd, whether in the pulpit or at the coffee shop, because it is he who continues to shepherd through them.

There is so much in seminary training that is necessary and profound, from training in exegesis, to homiletics, systematic theology, and practical ministry skills. And yet, in my experience, many pastors leave seminary feeling equipped to exegete a passage or preach a sermon, but don’t feel prepared to care for and counsel souls. What Talbot uniquely provides is an emphasis on the formation of the student, such that through their own life with the Lord they learn what it means to walk with him in such a way that they can minister faithfully and with longevity as those who rest in the work Christ is doing. The formation of a pastor’s soul is critical, because in everything a pastor does, who they are actually shows up and shapes their ministry.

There are many reasons I am excited to be back at a place that has meant so much to me personally, spiritually, and intellectually. But I am most excited about the fact that Talbot is committed to forming pastors who love the people of God in Christ by the Spirit. As director of the pastoral care and counseling program, I am excited to be a part of the renewed emphasis on Talbot as the seminary for pastors who want to pastor. In particular, I am thrilled to come alongside my dear friend Kyle Strobel, director of the Institute for Spiritual Formation, as we partner in the continued work of teaching and training students what it is to know the love of God deeply and to bear the fruit of that love as they preach, lead, and counsel souls in the local church.

Jamin Goggin (B.A. ’03, M.A. ’08, M.A. ’08) is an associate professor of Christian ministry and leadership at Talbot School of Theology. He has a Ph.D. in systematic theology from the University of Aberdeen.

Biola University

Biola University