Have you ever been through a long season when it seems your zeal for God has all but vanished? Have you ever experienced a stretch of time in which nothing motivates you to pray, God’s word is uninteresting, and very little excites you about the Christian life? If so, you’ve experienced spiritual apathy — a common but perplexing problem.

Part of what makes apathy perplexing is that it seems to take aim at meaningful things, spiritual things, things that are meant to give us life. Apathy is highly selective. And what often feeds our apathy toward the meaningful is a steady dose of the trivial. While there are many contributors to our spiritual apathy, I’d like to highlight triviality as one cause to which I find myself falling prey.

Numbed by Meaninglessness

One of my favorite songs from a movie in recent years is the catchy tune, “Everything is Awesome” from The Lego Movie. We’re first introduced to it in the film as the lead character, Emmet, recites a litany of everyday events in his life he deems “awesome”:

- Always use a turn signal

- Park between the lines

- Drop off dry cleaning before noon

- Read the headlines

- Don’t forget to smile

- Always root for the local sports team

- Always return a compliment

- Drink overpriced coffee

Emmet is so blind to the mundaneness of his life that he deems every lame experience as awesome. He has no real conception of what awesomeness really is. Driving the car, returning a compliment, or paying for overpriced coffee (“That’s $37 dollars,” says the barista. Emmet responds, “Awesome!”) — all of these are equally awesome. At the risk of taking all the fun out of a really fun song, I think Emmet and his little Lego world point to something about our own: we often lose touch with what is really meaningful. Everything is presented to us as momentous, worthy of comment, worthy of indulgence, so that our faculties become dull to the truly remarkable. We are numbed by triviality. If everything is awesome, everything ceases to be awesome.

In the foreword to his important book, Amusing Ourselves to Death, Neil Postman contrasts the nightmarish visions of two important dystopian writers — George Orwell (1984) and Aldous Huxley (Brave New World) — and through them paints a chilling picture of the dangers we face today.

What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture.

We live in both an Orwellian and Huxleyan world, yet it’s Huxley’s concern that’s most relevant for us as we think about apathy. The truth is we live in a trivial culture and, unfortunately, triviality numbs us to the meaningful. We live in a world in which big and small things, meaningful and meaningless events are given equal billing, and this has a deadening effect on us.

In one of my favorite standup routines, comedienne Ellen Degeneres shows her empathy for newscasters who regularly have to flit back and forth between stories of tragedy and feel-good pieces: “There were no survivors. … And next, which candy bar helps you lose weight? … Still to come, there’s an asteroid heading towards earth. … But first, where to find the cheesiest pizza in town!” How does anyone process this bombardment of the trivial, especially when the trivial is placed alongside the meaningful? When everything (marketable or entertaining) is awesome, what are we supposed to care about?

Everything and nothing. The problem with making everything important is that everything can become equally important. It becomes harder and harder to feel the bigness of something that really is a big deal. We are pummeled by triviality until we finally throw up the white flag and surrender to apathy. As Postman writes, “The public has adjusted to incoherence and been amused into indifference.” But, again, the indifference is selective; it takes aim at meaningful things. At a time when everything must be posted, liked, commented on, and retweeted, we are slowly conditioned to treat worthy things unworthily, or to stop caring about everything equally.

The Gospel Meets Triviality

We are drowning in triviality. No wonder we find ourselves losing perspective about what really matters. It’s no surprise that a soft nihilism — a fancy word for the feeling that everything is kind of meaningless — tends to creep in undetected, and we simply stop caring about important things. Yet, into this fog, God steps in.

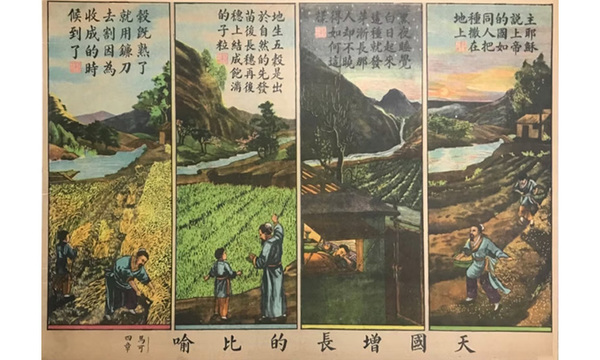

When Jesus’s disciples returned from a short-term mission trip feeling good about their ability to cast out demons, Jesus redirects them. He points them to what really matters: “Do not rejoice in this, that the spirits are subject to you, but rejoice that your names are written in heaven” (Luke 10:20). Similarly, when the disciples were enamored by the beauty and grandeur of the temple, he refocuses them by telling them about the end of history (Luke 21:5–36). He remarks that not a single stone of that glorious temple will be left standing when all is said and done. In other words, in light of the bigger thing that God is doing, Jesus is saying don’t focus on power, or wealth, or even beauty. These are not the major themes in God’s story. They are fleeting. The story of what God is doing is as old as creation: to reconcile all things to himself through Christ (Col. 1:20).

Part of the good news of the kingdom is that God invites us into a bigger drama and, in doing so, provides us with meaning, proportion, and perspective. He calls us back to what is truly awesome and away from numbing triviality.

Fighting for Zeal

Another aspect of the gospel is that God does not leave us alone in our attempt to regain a sense of meaningfulness in our lives. God gives us grace, not just as unmerited favor, but also as a source of empowerment. The apostle Paul writes, “[God’s] grace toward me was not in vain. On the contrary, I worked harder than any of them, though it was not I, but the grace of God that is with me” (1 Cor. 15:10). Notice that grace empowers hard work. It drives us to put forth a real effort in our fight for godliness.

When it comes to overcoming spiritual apathy, we really are in a fight. But the way to victory is through the slow but effective process of cultivating a heart that is less susceptible to apathy and one that is quick to respond to it when it arises.

I suggest two practices that can help cultivate meaningfulness in your life and undo the debilitating effects of the trivial.

- Practice silence. With all the noise in our lives, we need to make silence and solitude a priority. How else can we have the space to process our thoughts, our sense of calling, our values, our mission? We know that our Lord regularly went away for times of solitude and prayer (Matt. 14:13, 23; Luke 4:1–2; 5:16; 6:12). These silent times likely helped him prepare for difficult times ahead, to grieve, and to pray deeply. While we may want to plan times of extended solitude (maybe 24–48 hours), we may also consider injecting moments of solitude into our everyday lives. Perhaps we choose to not listen to anything on our 15-minute drive to work or 30-minute morning run. Small choices like these can help de-clutter our minds and free us up to reflect on what really matters.

- Practice gratitude. Thankfulness is a subversive antidote to triviality. Paul writes in Ephesians 5:3–4: “Let there be no filthiness nor foolish talk nor crude joking, which are out of place, but instead let there be thanksgiving.” Notice that thanksgiving undermines filthy, empty, trivial, and mocking talk. We replace triviality with gratitude to God. Calling out some of the good things we have from God immediately gives perspective to our daily lives. Paul elsewhere even suggests that thankfulness infuses meaning to every good gift God has given: “Nothing is to be rejected if it is received with thanksgiving” (1 Tim. 4:4). Start small by thanking God every morning for the everyday things like a warm shower, breakfast, family, a job, friends. Or, develop a weekly habit of writing down the things you’re thankful for. Experts have shown that those who write down what they’re grateful for display greater mental health than those who don’t.

May God help us grow in zeal for the things that matter.

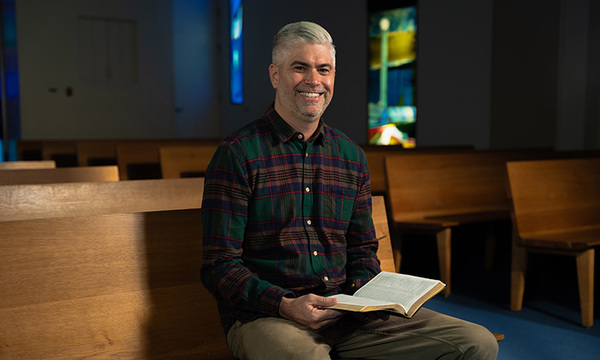

Adapted from Overcoming Apathy: Gospel Hope for Those Who Struggle to Care (Crossway, 2022) by Uche Anizor, Ph.D., associate professor and chair of undergraduate theology at Talbot School of Theology.

Biola University

Biola University