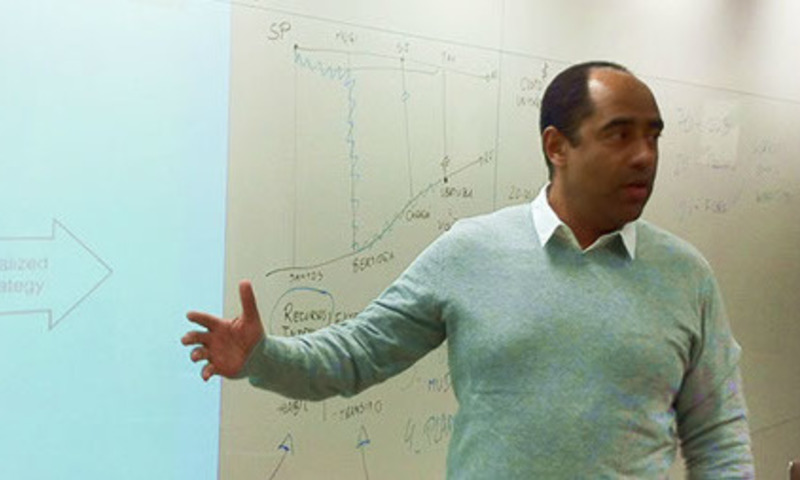

Wlamir Xavier, associate professor of international business and finance at Biola University, did not start his career evaluating international markets. He started on his career journey thinking he would become a chemical engineer. With more than 20 years teaching business finance, nearly 10 years doing marketing and more than five years owning his own consulting firm, he has a diverse portfolio of experience. He focuses his research on the business group phenomenon in emerging countries, corporate governance and non-marketing strategies. He has served as a visiting scholar at the University of Paris Dauphine, the Wharton School, the Copenhagen Business School, the University of La Sabana, Colombia and Chongqing University, China. Xavier is founder and vice president of the CW7 Group, a consulting firm that provides training on leadership and coaching to Christian churches.

Xavier shared more about his journey and thoughts on business with the Crowell School of Business.

Tell me more about your career before coming to Biola.

I was originally a chemical engineer. My initial idea was to be an engineer and to work in a plant. But after college, my first job was at IBM in the marketing department. So I've never worked as an engineer! Instead, I became a marketing manager (for six years), then a business owner and consultant (since 1998), and I’ve been a professor for the last twenty years, working and studying in Brazil, France, Denmark and the United States.

How did that happen? How did an engineer end up in marketing?

Back then, multinationals and big companies used to hire recent graduates and build them in their own image. They recruited from the best schools in the country, trying to find smart people to develop. They put us in trainee programs and inoculated us with as much IBM “firm” culture as they could. My class was 20 new graduates — system engineers, but also architects, other engineers, business administrators, and others — and they put us all in the classroom for seven months at full salary, just to study. After that, they allocated us where they needed us. This was 1988, when that was very common. Unfortunately, companies no longer do that. But that's why I went into marketing, and I stayed there for six years.

I got a graduate degree in business administration and left IBM to start my own company. I then got a second master’s degree — a master of science in production engineering — related to what my company was doing. Then I decided to pursue a doctorate in business administration because I was a business owner, and I thought a Ph.D. would help me run my company better. I was also considering becoming a full-time scholar because I had been serving as adjunct faculty for a few years.

I decided to take a post-doctorate; in the U.S. it might be called a second Ph.D. By 2014 I was teaching at a research-oriented university, with mostly graduate courses, and I was pretty sure that I wanted to become a full-time scholar. So I left my company behind and decided to move to the U.S. I took a graduate certificate in Finance because finance professors are scarce and it was something I liked, so I have this dual qualification to teach finance and business.

What courses are you teaching regularly at Biola?

This is my second semester, and I've been teaching courses on international business and finance, including the capstone international business course — the last course students take before graduating –— international finance, corporate finance, and economics, which is my base discipline for everything.

The U.S. is the biggest economy in the world. Wouldn't it be enough for them to say, “I'm going to focus just on learning about the U.S. market. That's all I really need to understand.”

Well, if you are able to give me an example of a single U.S. firm that is not deeply connected with international suppliers or technology or employees or markets, then I will just go home and retire. There is no such thing as an isolated market. Everything is interconnected. No matter what example you bring up — the phone you're using, or the computer, or the clothes that you're wearing — everything, some way or another, is connected to international partners, customers or suppliers. So it's very hard if not impossible to find a purely domestic company anymore. Our students need to know that. Even if a student chooses to work for their family business or a local business, they will need to have this kind of knowledge. It does affect them.

There is probably a lot of misunderstanding here about international business and about the rest of the world in general. How do you overcome that misunderstanding when you're teaching undergrads?

What I just mentioned, this kind of awareness, is an important first step. A second step that I believe to be necessary is giving them an idea of relevance. They might say back to me, “Okay, it's important, but how important?” So I always try to bring examples of external and international events and decisions that affect their daily lives. And right now you don't have to make a big effort to find news and events that prove this point. It's very, very current. So what I try to do is to bring what's going on in the world into the classroom, so that they experience and understand that these events affect their lives, not just as a student seeking a job in a couple of semesters, but after that, as a consumer, as a citizen, as a person. So that's what I try to do, to show relevance.

One of your papers is about sustainability and the environment and cattle in Brazil. The argument is often framed as, “You have to choose between environmental sustainability and economic viability.”

I do not believe this has to be a trade-off. I believe you can be sustainable from an environmental standpoint and from an economic standpoint as well. This particular research was related to finding ways to use solar energy on cattle farms without damaging either the environment or the industry. So it was an economic study showing you can use solar panels as a way to collect low-cost renewable energy, and the solar panels served as shelters for the cattle, which actually improved their health and productivity.

So it was just a simple exercise of showing how to create ways to make technologies work. You don't have to necessarily think in terms of trade-offs. That's the relevance of working and thinking in an interdisciplinary way, which describes most of my research; trying to connect and bridge different disciplines to try to get them working together. That's why I do international business.

Some of these might be complicated concepts for undergraduates. How do you make them more accessible?

The idea is to try to simplify, to use simpler terms and also to provide examples and (as much as possible) experiences. For graduate courses, the students are more mature, and they’ve often had some job experience. For undergrads, I try to frame these apparently complex realities in simpler terms. In the classroom, I like to use gamification. I like to use simulations as well. I like to offer a lot of interaction and one that I like most is learner-to-learner interaction, so the model isn’t where the lecturer knows everything and he just pours knowledge over the students. No, we talk, we interact. And when a student interacts with another student, they share their understanding but also their doubts, and they help each other through. I can explain a concept in ten different ways, but to hear it from a fellow student, in terms and language and references they both understand, that helps so much. So you've just become a learning community, rather than one wise person trying to pour out knowledge.

What's your favorite thing about being here at Biola?

Oh, that's an easy one, because I've always worked in secular institutions when I had to hide my faith. So here, for the first time, I know I'm not only allowed but encouraged to put together my faith and my academic discipline. So this faith integration is for me the most appealing aspect of being here, of being able to openly disciple and provide personal support based on my faith, not knowledge alone. I can openly invite the Holy Spirit to the classroom on a daily basis.

To learn more about the international business concentration at Crowell, visit Crowell’s website. To learn more about Professor Xavier, visit his profile or his website.

Biola University

Biola University

.jpg)

.jpg)