Faculty, students and young alumni are not just learning about science in the classroom. They’re doing science in the laboratory. As Biola prepares to construct a new building that will greatly amplify the university’s science research potential, here is a snapshot of the impressive work already being done.

Why Being A Night Owl Is Hazardous To Your Health

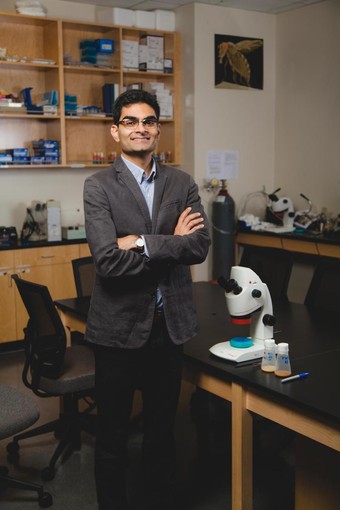

What can mice and fruit flies teach us about the dangers of being a night owl? Quite a bit, according to the research of biological sciences professor Behzad Varamini.

Since completing his Ph.D. in nutritional science from Cornell University in 2009, Varamini has been interested in the ways that natural circadian (daily) rhythms of light, dark and sleep affect overall health. As a post-doctoral scholar at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School, Varamini’s laboratory research focused on nutrient regulation and metabolism. Returning to the University of Pennsylvania every summer to continue ongoing research projects, Varamini’s latest interest focuses on how circadian rhythms of light and dark affect metabolism.

Looking at the issue on the gene expression level, Varamini’s research (using mice and fruit flies) seems to agree with what doctors have known for decades: that “humans who choose to rebel against nature’s created order of day and night cycles endure havoc.”

People who work night shifts and sleep during the day, or insomniacs who are awake at night, are far more likely to be overweight and obese, as well as more prone to depression, heart disease, cancer, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, said Varamini.

Varamini’s research looks at how environmental cues like light affect how bodies process food. If two people eat the same exact diet but one goes to bed earlier and the other is a night owl, for example, the person who goes to bed earlier will probably store their calories less as fat and burn calories better than the night owl. Eating calories within an 18-hour window, or midnight snacking, causes more energy to be stored as fat than eating in a 12-hour window.

“What’s clear is the more we can align our behaviors with the cycles of nature and with life cycles, the healthier we are,” said Varamini, whose work with fruit flies shows that disrupting their sleep impairs memory, accelerates aging and shortens lifespan by half.

Through a directed research class on gene expression, Varamini has involved six Biola students in his experiments with fruit flies. He hopes to have them submit an abstract for a presentation on the research at Experimental Biology, an annual conference being held this year in San Diego. A longer-term goal is to publish something on the research and have Biola students’ names on the paper, something that can help them get into competitive graduate programs.

Varamini’s research has practical health implications but also spiritual resonance. The fact that God made days with a certain 24-hour length and that our bodies are so wired to thrive on that precise rhythm shows that we were made for this world, he says.

“What has been made clear is that rebelling against the created order wreaks physical havoc,” Varamini said. “Living ‘in sync’ with the created order, sleeping and eating at set times, leads to physiological harmony — rebellion leads to accelerated disease and death.”

Clinical And Laboratory Research In Indonesia

For the past two summers, Biola professors and students have received hands-on, cross-cultural experience in global health through a partnership with Pelita Harapan University (UPH), a Christian university outside of Jakarta, Indonesia. As part of a nearly month-long experience, students shadow medical professionals at Siloam General Hospital (SGH), the teaching hospital of UPH’s medical school.

“Eight Biola students were able to act as basically first-year medical students, rotating through different departments and seeing the practice of medicine in different fields and environments,” said biology professor Harvey Havoonjian, who helped develop the partnership with UPH.

Students stay in campus housing at UPH and also participate in cultural immersion experiences as part of the program. This past summer, the program included a research component as well, with four Biola students working in the Mochtar Riady Institute for Nanotechnology (MRIN), a UPH-affiliated biological sciences lab investigating the anti-cancer properties of Newcastle Disease Virus (NDV). The four Biola students spent the spring semester at Biola in a directed research course on molecular techniques, learning key skills and practicing lab procedures in preparation for the research in Indonesia.

The research experience at MRIN in Indonesia provided a valuable first-hand look into the day-to-day life of a full-time laboratory researcher, said biological sciences graduate Kendall DeKreek (’15), one of the four Biola students who worked full days in the MRIN lab while on the trip.

“Opportunities to engage in full-time lab work are hard to come by as an undergrad, so I’m very thankful for having been able to participate in this experience,” he said.

A total of 12 students (four doing research and eight doing hospital shadowing/rotations) went on the trip in 2015 and another 12 will go in the summer of 2016, representing majors like biological sciences, human biology, biochemistry and kinesiology.

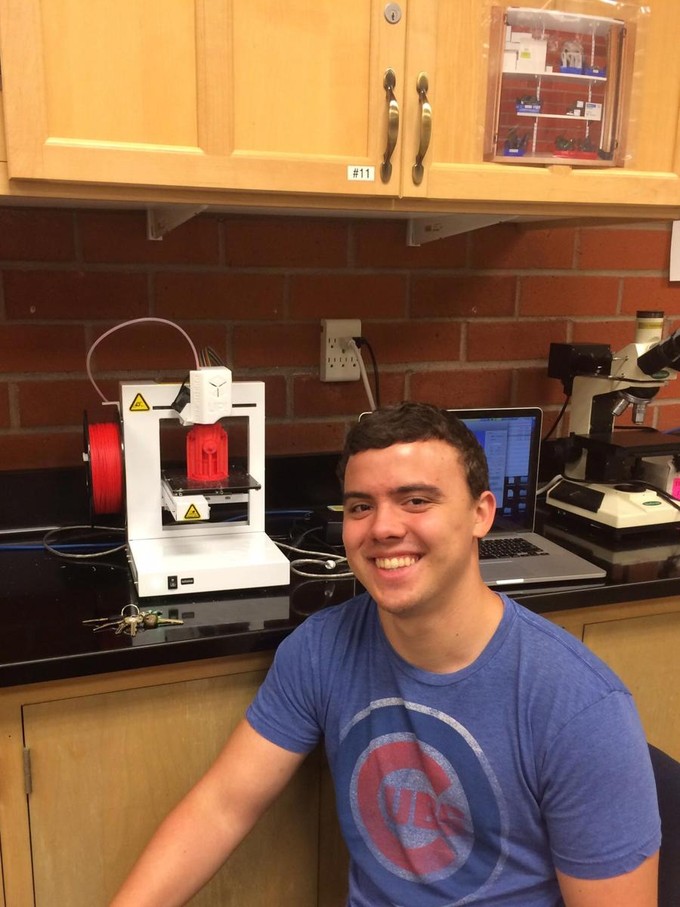

3D Printing With The Help of Milk Jugs

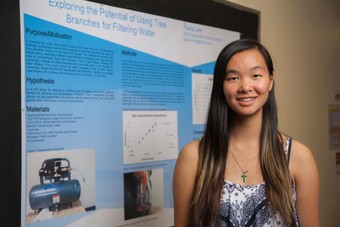

Exploring Tree Branches As Natural Water Filters

After reading an article published by MIT about using tree branches as a cost-effective method of filtering water, Lee decided to explore the phenomenon in her own research. Under the guidance of professor Albert Yee over the summer, Lee attempted to study and observe xylem filtration by focusing on the factor of aging in tree branches.

“I wanted to observe how the branch’s filtering capability was affected as the cut off branch got older,” said Lee, who plans to present a poster of her research at the chemistry, physics and engineering department’s “Solving World Class Problems” event.

Why Some Raccoon Intestines Are More Welcoming to Parasites

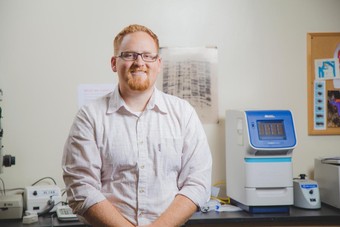

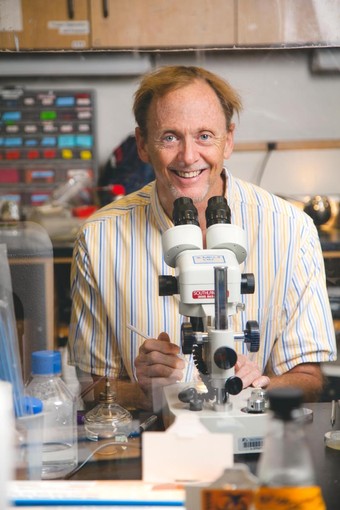

For the past four years, biological sciences professor Matt Ingle has been researching Raccoon Roundworm, an intestinal parasite common to raccoons — one that’s known to infect other animals and even humans with sometimes-fatal results. Ingle’s work on the parasite focuses on raccoon genetics and hopes to contribute to the better understanding of the transmission of the parasite and what genetic elements make certain groups of raccoons more or less susceptible to the parasite.

For the past year, Ingle has had about 20 Biola students working with him on the project. This summer, he took three of them to the national meeting of the American Society of Mammalogists in Jacksonville, Fla. While there, they presented some of the work on the relationship between raccoon genetics and the parasite, as well as a poster on the parasite in non-raccoon hosts.

Some of the students Ingle has worked closely with on this research are heading toward a graduate degree or medical school, so having the opportunity to participate in original research is helpful in a number of ways.

“It really helps students develop their problem-solving abilities, as well as their ability to communicate with other researchers and through writing abstracts that get reviewed by a committee,” Ingle said. “It’s helpful regardless of where you go in the field.”

The Mysterious Longevity Of Mutant Worms

Worms are among the most abundant organisms on the planet and have been well studied in recent decades. But some worms have longer lives than others because of genetic mutations, and biological sciences professor Matt Cruzen is interested in finding out why.

Cruzen’s research focuses on the relationship between caloric restriction and lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans, a species of nematode worms. The typical lifespan of one of these tiny worms is only 16 days, but some nematodes can live up to 35 days. Cruzen is interested in studying the genetic mutations in worms with longer lifespans to see what causes them to eat less and expel less energy, which leads to longer life.

A handful of Cruzen’s students are highly involved in the research process and work with several different genetic strains of nematodes. They learn to study the worms in the lab in order to characterize their genetic mutations that affect lifespan. So far, the students have found that a certain strain of mutated nematodes has a tendency to eat less. Using a scanning electron microscope to view the worms, students are able to count the number of times each worm pumps food through its mouthparts in one minute. They have found that longer-living nematodes do pump significantly less food than do worms with an average lifespan, demonstrating a relationship between caloric restriction and lifespan in the nematodes.

The research is ongoing for Cruzen and his students, who will next be looking at how nematode lifespan is affected by “brood size” (how many eggs they lay). Cruzen’s students have published some of their nematode research and present their findings annually at the Biola science symposium.

Studying Mice To Understand Pain Management

Because Biola currently lacks the science lab facilities to accommodate certain types of research, some science students at Biola have sought opportunities to gain lab research experience off campus.

Joseph Lee, a junior biological sciences major with pre-med concentration, has been doing research at the University of California, Irvine School of Medicine. Working in the Department of Anesthesiology and Pharmacology, Lee’s research focuses on the molecular mechanisms for chronic pain management. His work involves transgenic mice and seeks to find a better control on the clinical understanding of pain by identifying genes that may be molecular determinants of a specific chronic pain state and serve as a target for the development of more specific and safer painkillers.

Over the summer Lee emailed various doctors and researchers, hoping to gain exposure to the research in the field of medicine. In that process he got connected to the UC Irvine project. This fall he has worked on this research at UC Irvine for 14 hours a week or more. He says Biola has prepared him to apply for medical school in the coming year, where he hopes to pursue a career in surgical specialties and work as a physician in an underserved community.

Helping To End World Hunger — By Studying Plant Growth

Over the past year, alumna Kelby (Songer, ’14) Schaeffler has been spending six to eight hours each week doing research in a lab at the California Institute of Technology, one of the world’s most respected research universities. Since first getting connected to the lab by Biola biology professor Jason Tresser, Schaeffler has been studying the developmental mechanisms of plants, specifically in the shoot apical meristem (SAM), using the Arabidopsis thaliana plant. Schaeffler assists one of the postdoctoral researchers in the study of cytokinin signaling pathways in the SAM, specifically how two particular peptide ligands signal and give feedback to one another, determining the size of the plant and controlling leaf and flower development.

Professor's Research Published In Leading Scientific Journal

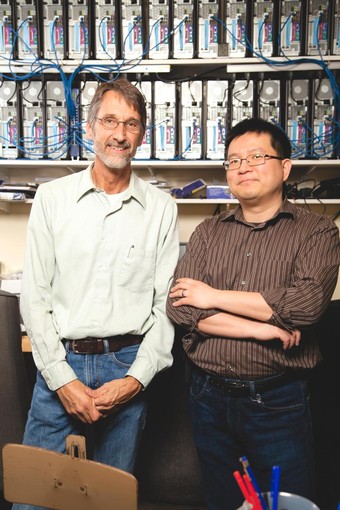

Earlier this year, physics professor Xidong Chen published a paper in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the official journal of the National Academy of Sciences and one of the world’s most-cited and comprehensive multidisciplinary scientific journals.

Professor Chen’s paper concerned oxidation-driven surface dynamics and is based on experiments conducted with collaborators from State University of New York and Brookhaven National Laboratory. Chen was in charge of developing a theory to understand and explain experimental results. An important result of his efforts was demonstrating a connection between the Hele-Shaw problem and surface dynamics on solid surfaces.

In addition to this impressive publication, professor Chen has recently been working with students on atomic force microscopy studies of ciliary structures of tetrahymena and surface structures of cancer cells. One of Chen’s student researchers, Sarah Lum (’14), presented results of their research to the Materials Research Society in the spring of 2014. Partly because of her work with AFM, Lum was awarded a sizable scholarship from the University of Notre Dame, where she is now pursuing a Ph.D. in analytical chemistry.

Fluorescence Spectroscopy With A Supercomputer

Biola University

Biola University