How are we to think about a God who commands genocide? I will begin by presenting four different propositions:

- God is good and compassionate.

- The Old Testament is a faithful record of God’s dealings with humanity.

- The Old Testament describes events that are identified as genocide.

- Genocide is always evil.

Since we cannot have all four of these together at the same time, scholars have sought to solve the problem by denying one of these propositions, as seen below:

- Reevaluating God

- Reevaluating the Old Testament

- Reevaluating the interpretation of the Old Testament

- Reevaluating genocide in the Old Testament

The first category is that of the New Atheists, who recommend that we solve the problem by rejecting both the Bible and the God of the Bible. The second category continues to follow God and view his Word as authoritative but rejects the violent portions of the Old Testament through such arguments as the lack of historicity (the events of Joshua never happened) or reading the Old Testament through a pacifistic Jesus-lens that encourages us to reject the violent portions of the Old Testament on ethical grounds. Most scholars in this category also deny inerrancy and remove (or reduce) judgment of any kind. The third category solves the problem by denying the text describes genocide at all. Instead, these scholars (mostly evangelicals) argue that the text’s violent imagery is only metaphorical or that the “massacres” are in reality only normal military battles.

This essay will focus on the fourth category, which recognizes the events in the Old Testament as those that would be reprehensible under normal circumstances, but were commanded by YHWH for that specific time and place for particular reasons. Scholars have proposed several lines of argument within this category, but I find three of them particularly helpful.

First, the Canaanites were not an innocent people, but the land “vomited” them out because of their sin (Lev. 18:25; Deut. 9:4–5), and YHWH had given them centuries to turn from their sins (Gen. 15:16). However, we should be careful to identify ourselves with those characters being critiqued in the text as well as those who follow YHWH: we should not condemn the Canaanites without first reminding ourselves that their fate is what we deserve as well. We are not “better” than the Canaanites.

Second, this destruction of the Canaanites was not based on ethnicity, but on their attitude toward YHWH. As the conversion of Rahab to a follower of YHWH showed (Josh. 2), any person (even a Canaanite prostitute!) could follow and obey YHWH. On the other hand, the death of Achan illustrates that if the Israelites act like Canaanites, then YHWH will treat them like Canaanites (Josh. 7).

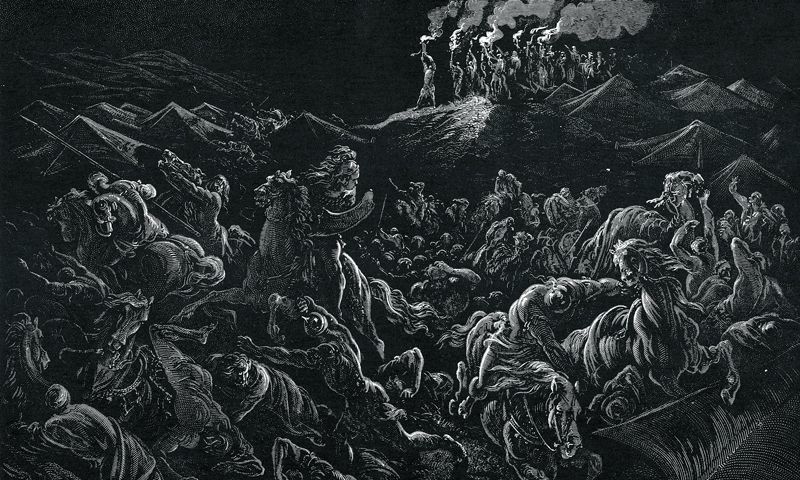

The third point, which we will examine for the rest of the essay, is that the commanded destruction of the Canaanites should not be ascribed to God having a “bad day,” but fits into the overarching plan of God for the world. Ever since Genesis 3, YHWH has been actively engaged in restoring his creation and removing injustice. In the flood, YHWH decisively demonstrated to the world that he would not tolerate sin, especially sin that damaged the image of God on earth (Gen. 6–9). YHWH judged Sodom and Gomorrah to remind the world that even though YHWH had promised not to destroy the world through a flood, he was still passionately opposed to sin, once again focusing on sins of injustice that enriched the oppressor (Gen. 18–19). Many centuries later, YHWH unleashed his full arsenal against Egypt — the most powerful empire in the world — when they oppressed Israel (Exod. 1–15), fulfilling his promise that he would curse those who cursed Abraham’s descendants (Gen. 12:1–3). However, the same hand of YHWH that had defeated the Egyptians (Exod. 9:3) would also kill an entire generation of Israelites in the wilderness when they disobeyed YHWH and acted sinfully (Deut. 2:15).

It is at this point that the commanded destruction of the Canaanites began. The Canaanites were free to stay and serve YHWH if they desired (Rahab is an example), but YHWH would not permit idolatrous peoples to stay in the land with his holy people Israel to lead them away from him and into injustice. The sobering book of Judges emphasizes divine judgment against Israel as they became progressively more Canaanite, though YHWH also acted in powerfully direct ways to rescue the Israelites whenever they repented. Many years later, YHWH handed the northern kingdom (Israel) over to Assyria because of their persistent injustice and idolatry (2 Kings 17), but the angel of YHWH destroyed the army of Assyria when the Assyrian king Sennacherib attacked the righteous Judean king Hezekiah and called out to YHWH for help (2 Kings 19). Ultimately, YHWH handed the southern kingdom (Judah) over to the Babylonians because of their persistent sin (2 Kings 24–25). Jeremiah referred to the exile as a herem, the same term used to describe the destruction of the Canaanites (Jer. 25:9). However, this exile to Babylon, as traumatic a national “death” as it was, would not be the end, and the return from exile under Persia was a “resurrection” of the nation in their homeland.

Many years later, Jesus’ teaching on hell built on the judgment texts described above. YHWH is still concerned about injustice and idolatry, and judgment lies in store for those who continue on in those sins without repentance. In a sense, the judgment texts in the Old Testament (like the flood, Sodom and Gomorrah, and the destruction of the Canaanites) were historical pictures of eschatological judgment demonstrating God’s hatred of sin and injustice. Since we are all sinful, we all deserve the fate of immediate death that Sodom and Canaan faced if it were not for the common grace that YHWH grants to humans, allowing us to live for a period of time on earth. This common grace is not something that he is required to give, but is a gift to humans. In the case of Canaan, he removed that common grace and brought their eschatological judgment to them immediately.

This reading of the destruction of the Canaanites is supported by the eschatological associations commonly made between the promised land and heaven (Heb. 3–4; Rev. 21–22). If the conquest has positive eschatological connections foreshadowing the eternal destiny of YHWH-followers, then it would not be surprising to see eschatological connections with judgment as well. While the New Testament does not connect the Canaanite conquest with eschatological judgment, authors in several places employ the flood and Sodom in this way (2 Pet. 2:6), encouraging a similar reading of the conquest. As Joshua Butler argues in his book The Skeletons in God’s Closet, in the eschaton, or the end of the world, YHWH will “get the hell out of earth” through removing from new creation those who insist on spreading injustice (that is, the power of hell and sin from earth) to allow his people to live as renewed images of God. In a similar way, YHWH prepared the land for his people Israel to follow him. As Judges demonstrates, when they did not remove the idolatrous influences, they were led astray from following YHWH and oppressed the weak.

It needs to be said clearly that the commanded destruction of the Canaanites was limited to that time and place and is not to be repeated today. Likewise, eschatological judgment is the work of God, not God’s people. However, the church’s responsibility is to keep herself holy. Ezra employed the herem language of the Canaanite destruction to describe the banishment (not death) of certain sinners from the community (Ezra 10:8). Paul likewise employs the Greek word anathema, which was frequently used in the Septuagint as the translation for herem, when stressing the need to keep the church holy from false teachers and those who did not love God (Gal. 1:8–9; 1 Cor. 16:22).

YHWH’s commanded destruction of the Canaanites is a difficult topic in the Old Testament, and even though I have studied it extensively, I still feel ill at ease with it. I find myself sympathizing with the disciples after Jesus instructed the people that they needed to eat his flesh, which caused many to turn away from him. When he asked his disciples if they were also going to leave, Peter responded by asking where else they would go (John 6:68), highlighting both their unease with his words and their desire to stay with him. But looking at the broader picture of YHWH’s plan for the world reminds us that the Canaanite destruction was one part of his plan to highlight his hatred of the world’s injustice and his desire to restore creation, encouraging us to examine ourselves and inspire each other to live holy lives before God.

Biola University

Biola University